For years after Vietnam, Spencer’s life followed a simple, destructive rhythm — work, drink, sleep, repeat. The whiskey was his shield, the haze his refuge from the ghosts that refused to leave. They came in the form of faces, voices, and the Mekong Delta’s heavy, wet air that seemed to seep into his dreams no matter how far away he was.

Tyler’s face was the sharpest of them all. His best friend, the man who had pulled him from the wreckage of a downed helicopter, was frozen forever in that last day they fought together. Talking about him felt impossible. Remembering him without the burn of alcohol felt worse. So Spencer didn’t talk. Didn’t remember. Not sober, anyway.

Then came the letter. The envelope was plain, but the return address stopped him cold: Mrs. Eleanor Vance, Arlington, Virginia. Inside was the news — Tyler was to be awarded the Medal of Honor, posthumously. The White House wanted Spencer there. It should have been a moment of pride, but pride was tangled with guilt, and guilt was something whiskey handled better than Spencer did.

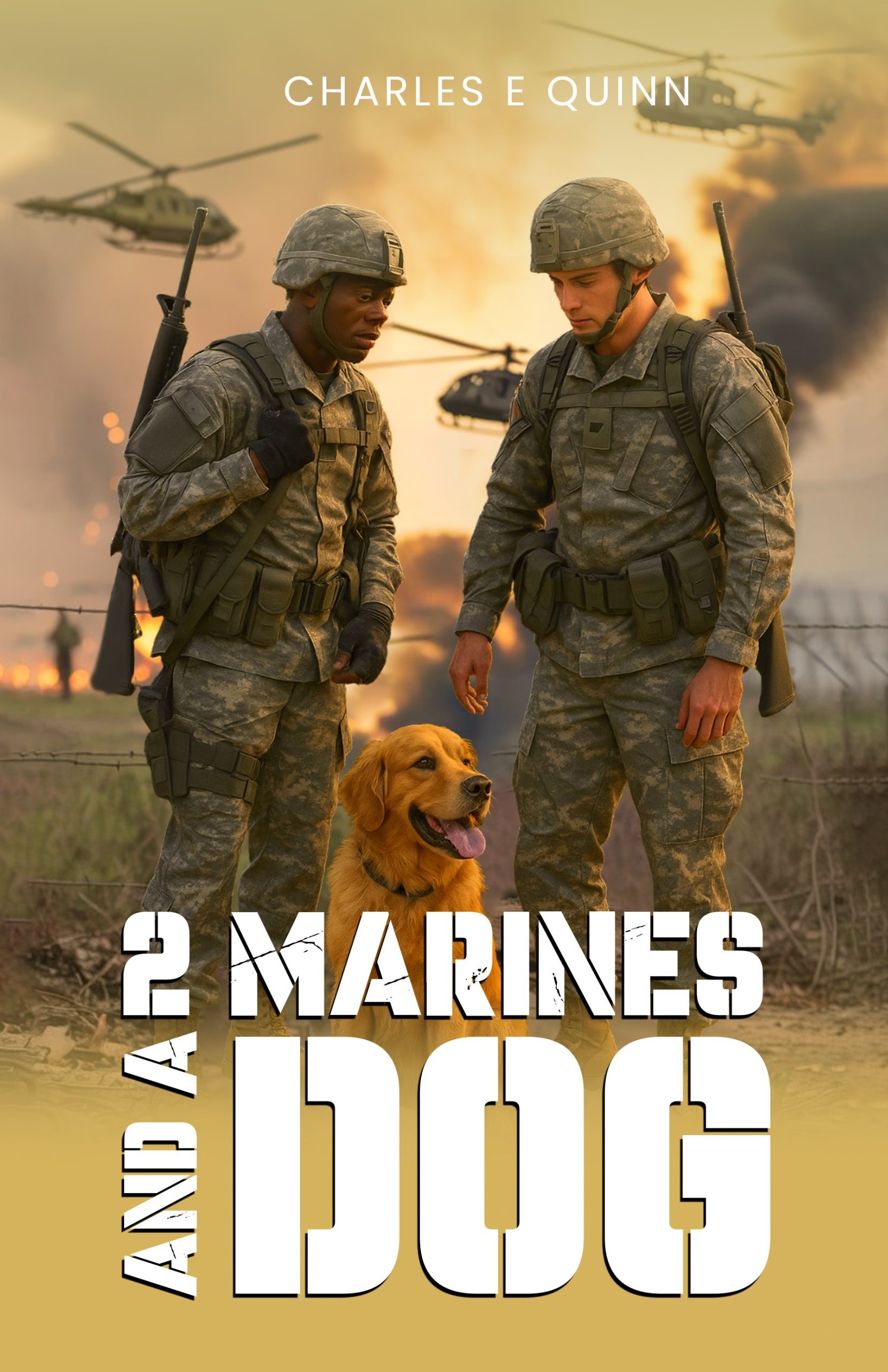

In 2 Marines and a Dog by Charles Quinn, this moment hits with the weight of both history and heartbreak. Quinn writes not just about the ceremony, but about the inner war it sparked — the battle between honoring a fallen friend and facing the wreckage of his own life.

On the day of the ceremony, Spencer left the bottle behind for the first time in years. The ghosts came with him, of course, but so did something else: a flicker of purpose. Standing in the room as Tyler’s medal was placed in his mother’s hands, he felt the past pressing in, but also the possibility of a future where he didn’t have to drink to keep the memories at bay.

The whiskey, the ghosts, and the Medal of Honor — they were all part of the same story. One of loss, survival, and the slow, painful crawl toward redemption. Because sometimes, the bravest thing a Marine can do isn’t running toward gunfire. It’s deciding, after everything, to start living again.