The train was supposed to be just transportation — a way to get from one point to another. But for Spencer, it was something more. It was a bridge between two worlds: the one he had been trapped in for years, and the one he might still have a chance to reach.

The letter had come days before, heavy with meaning. Tyler’s mother had invited him to Washington, D.C., for the Medal of Honor ceremony honoring her son — his best friend, the man who had once pulled him from the wreckage of a downed helicopter in Vietnam. The invitation should have been an honor. Instead, it felt like a reckoning.

For two decades, Spencer had been living in the shadow of the Mekong Delta, battling an enemy no one could see. He survived the firefights, the jungle, and the killing fields, but coming home had left him adrift. Nights were filled with nightmares; days with a haze of whiskey and regret. Friends drifted away. His marriage cracked under the strain of silence and sudden bursts of anger. He avoided anything that might pull the memories too close. Until the letter.

That’s how he found himself on a platform, a duffel bag at his side, watching the train pull in with a slow, metallic groan. He could have driven, could have flown, but the train felt right — slower, more deliberate. Maybe he needed the miles to think.

Inside, the car was filled with a mix of strangers: a couple whispering over coffee, a businessman typing furiously on a laptop, a child pressing his face to the glass. Their lives felt light, untouched by the kind of memories Spencer carried. He sank into his seat, the steady rhythm of the tracks beneath him like a heartbeat — constant, grounding.

As the landscape blurred past, he caught himself drifting between worlds. One moment he was watching golden fields roll under the late afternoon sun, the next he was back in the Delta, wading through mud that pulled at his boots like it wanted to keep him. The war was never far; it just waited for moments of stillness to creep in.

But somewhere between the small towns and the stretches of open land, something shifted. Maybe it was the rhythm of the train, maybe it was the distance from his apartment’s stale air and the bottle sitting on the counter. For the first time in years, he thought not about how to forget, but about how to remember without it breaking him.

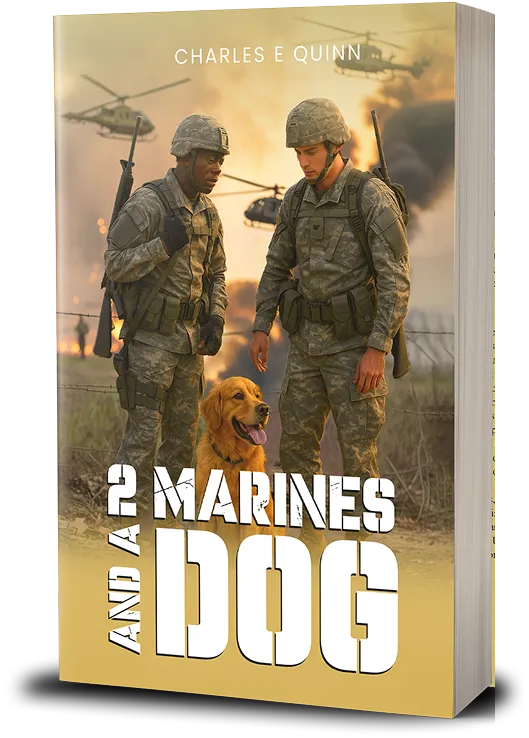

In 2 Marines and a Dog by Charles Quinn, this train ride becomes a quiet turning point. It’s not about grand gestures or sudden healing. It’s about the slow realization that the road to redemption isn’t a leap — it’s a series of steps, and sometimes those steps are laid out on steel rails.

By the time the train began its final stretch into Washington, Spencer wasn’t “fixed.” The ghosts were still there. But the man who stepped off onto that platform carried something he hadn’t in a long time: the faint, fragile belief that maybe, just maybe, he could survive the life he had left.