Long before Spencer was a Marine, long before the Mekong Delta and the rifle in his hands, he was a boy growing up in a Boise house where silence was a second language. His father’s whiskey glass was never empty, his mother’s eyes never met his for long, and conversations felt like negotiations with an invisible wall. Love, if it existed there, rarely spoke its name.

He learned early how to read the room without making a sound, how to disappear into the background when tempers shifted. When his sister left abruptly at seventeen, the family barely spoke about it. In that house, absence was easier to live with than truth. Spencer carried that quiet with him everywhere, a survival skill that would later serve him in a different kind of war.

When Vietnam came calling, it was less a decision than an escape. The jungles were a far cry from the dust motes of Boise, but in both places, danger demanded you stay alert. In the killing fields of the Mekong Delta, silence was a weapon — and Spencer had been training for it his whole life. Moving through the undergrowth, holding his breath as enemy soldiers passed within feet, he felt a grim familiarity: the art of vanishing, learned in childhood, now keeping him alive.

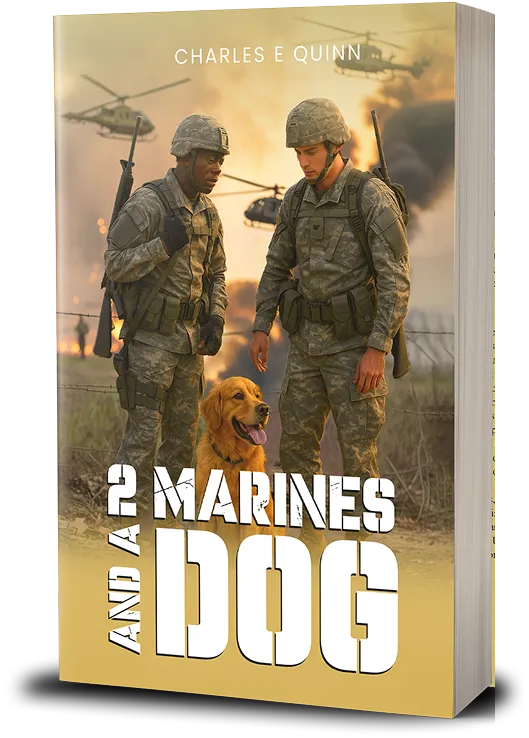

In 2 Marines and a Dog by Charles Quinn, these parallels are drawn with raw honesty. The skills that protected Spencer as a boy became the instincts that kept him breathing in a war zone. But they came with a cost. When the war ended, and he returned to a world that expected noise, connection, and normalcy, those same instincts turned into barriers.

The killing fields were brutal, but they were straightforward — survive, or you don’t. Back home, there was no clear enemy, only the echoes of both wars he had fought: one in the jungles, and one in the quiet, airless rooms of his past. And in some ways, it was that first war, the one in Boise, that proved hardest to survive.